November is Native American Heritage Month. What started at the turn of the century as an effort to gain a day of recognition for the significant contributions the first Americans made to the establishment and growth of the U.S., has resulted in a whole month being designated for that purpose and a proclamation from George H. W. Bush in 1990 calling upon “Federal, State and local Governments, groups and organizations and the people of the United States to observe such month with appropriate programs, ceremonies and activities.”

November is Native American Heritage Month. What started at the turn of the century as an effort to gain a day of recognition for the significant contributions the first Americans made to the establishment and growth of the U.S., has resulted in a whole month being designated for that purpose and a proclamation from George H. W. Bush in 1990 calling upon “Federal, State and local Governments, groups and organizations and the people of the United States to observe such month with appropriate programs, ceremonies and activities.”

We have some catching up to do here in Camden, but we are so far behind that it seems no one knows where to start.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Camden natives, and what it means to be one. Terms like Camden native and “from away” get thrown around in political disagreements about things like sidewalks and school funding, but the fact is that most true Camden natives were driven out long ago. I’m not talking about the ones who moved to Union to get away from all the hippies who moved here in seventies and eighties. Their families may have been here a few generations more than others, but it’s all pretty inconsequential in terms of the history of the land we inhabit, where a culture and ecosystem endured and evolved for thousands of years before us.

In the same spaces where we squabble about tourist attractions, parking spots, picnic tables and honoring our history, a larger story and a longer history hangs heavy. The things that we call historic are but tiny blips in the story of the land we occupy, the Megunticook River Valley, carved out between mountains by the receding glaciers some 13,000 years ago and populated by the people whose memory lives only in the names of a few of our favorite places. This is the ancestral hunting and fishing territory of the Penobscot and Abenaki people, and their traces can still be found sprinkled among the ashes and buried in the mud.

Camden’s first permanent European settler, James Richards, is said to have sailed into Megunticook Harbor with his family 253 years ago. The details of this era in Camden history are poorly documented and leave much to the imagination, but it’s often where the telling of Camden’s history begins and we’ve fallen into the habit of repeating as fact the misstatements. We tell our kids that Mount Battie was named after Betty Richards and that Negro Island (later renamed Curtis Island) came from a comment made by the unnamed African cook who arrived with Richards and his family.

Really? Camden’s first settler was a slave owner? Did they all have slaves? If so, where are they buried? Very little has been documented that supports the fable, but still it is repeated. All of Camden’s serious historians, most of them from away, have noted how poor the record keeping was among the early Europeans. They were just trying to stay alive and struggled to keep track of their own history, never mind document what came before them.

George Weymouth, who is known for his early explorations of Penobscot Bay at the beginning for the seventeenth century, came at a time when a great number of indigenous people still lived here. In his efforts to colonize the land, he kidnapped several of the natives and brought them back to England. If only we could have convinced him of the great value it might have been to just leave them alone and learn the history of our beloved region through their eyes. What stories did they tell their children? What secrets had the mountains revealed to them? Beautiful paintings have memorialized Weymouth’s voyage and his ship, the Archangel, but how have we remembered the people that he disrupted? The question is a nagging one that has come up before, but not often enough in Camden.

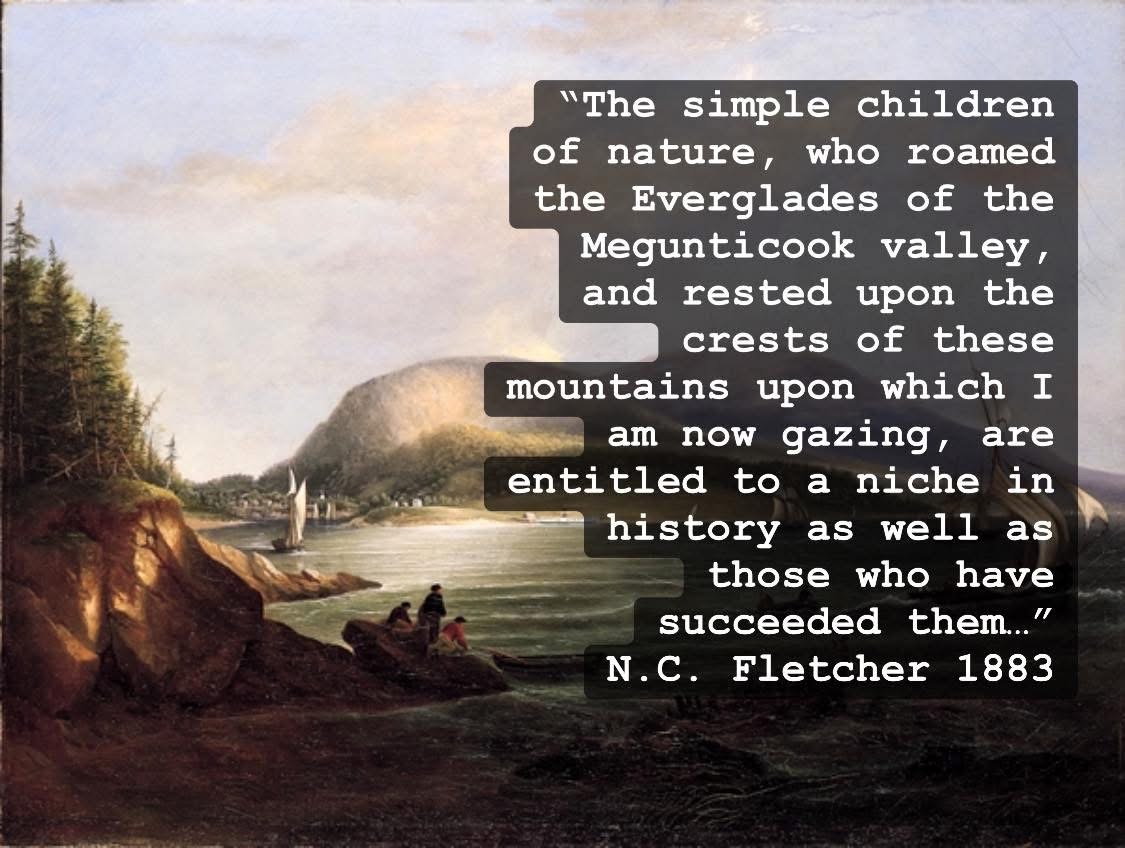

The following is from a column by Nathan C. Fletcher published in the Rockland Opinion in 1883 (credit goes to Barbara Dyer for the fact that anyone knows about Fletcher’s writing at all). His son built the building known as the Fletcher Block about 10 years later (now home to Boynton McKay). In a series of columns for the newspaper he commented on the many inaccuracies and omissions in the town’s historical record, and produced what might be considered Camden’s first and only land acknowledgment statement.

“The Indians in great numbers met Captain Weymouth and his company, when they landed upon our shores, in a friendly manner and brought their furs to exchange for trinkets of but little value; and the Englishmen repaid them by invading their humble wigwams, and wrenching from the mother’s fond arms the best beloved boy, and from the father the girl, the delight of his eyes, who cheered him in his lonely hours in his embowered wigwam, when returning from his hunting grounds. The simple children of nature, who roamed the Everglades of the Megunticook valley, and rested upon the crests of these mountains, upon which I am now gazing, are entitled to a niche in history… I have been led to speak of those who preceded us in peopling these regions, when Camden was a solitude, as was the group of islands before me; which gracefully rest upon the peaceful waters of ‘Penobscot bay,’ as an act of simple justice and to leave on record my utter detestation of the villainous conduct of those freebooters…”

I have found nothing so strongly worded in any historical writing or commentary since Fletcher and if anything, our view of history seems to have condensed rather than expanded as a community. In Camden, honoring our history is mostly about the last hundred years or so, and even then, the emphasis is inconsistent and the oral histories are foggy and often contradict the source documents. The word historic, in Camden seems to evoke notions of dazzling homes on Chestnut Street or flower pots hanging from lamp posts…. We talk about the Village Green, the library, Harbor Park, all of which were designed less than 100 years old.

Even the story of James Richards and the struggle to survive has mostly been omitted from the narrative, but at his time there were still a few of the Wawenock tribe living in the area and although they are said to have coexisted peacefully with the new settlers, we don’t know much other than they would sometimes come and use the sharpening tools outside his doorstep.

According to Camden’s earliest history book, a few sites during James Richards’ time were said to have still been occupied by the Wawenocks. One of these was Eaton’s Point, as it was called. It is still a place notable as a landmark in the general vicinity in front of the condos in between Lyman Morse and Steamboat Landing. There is sizable boulder there too that once defined the northern boundary of Camden and it can still be seen right where the surveyor said it was in 1768 (I’m about 85% sure), cast down from the mountains by the receding of the glaciers and no doubt employed as a waypoint for thousands of years before us. Our deepest connection to history is looming large above us in the mountains, scraped in the bedrock by glaciers, buried in the soil beneath our feet.

A few people like Kerry Hardy and Harbour Mitchell have done more than most to prod us into more careful examination of our past. In many cases, a better understanding of the natural history of the region is the best starting point. The remnants of clam flats have been found in the soils at the outlet of Megunticook Lake, reminding us that all of Camden was once an ocean. Arrowheads along the banks of Dailey Brook and the early maps speak to a time when Camden Harbor’s intertidal zone extended nearly all the way to Route 1. The shape today is the result of a combination of dredging out of native clam flats and the importing of soil to fill in around the edges. Most of our streams have been dammed or blocked with culverts, so radically altering the habitat as to render them unlivable for many native species like Brook Trout.

Still, there are a few places that true Camden natives can be found hiding out in the cold waters that descend from the mountains, cascading naturally over the rocky ledge that connects us with the true native people of the region.

In the vicinity of Quarry Hill, Don Rainville and his wife Michelle stumbled upon some of Camden’s most ancient artifacts, some dating back 5-7,000 years, during a renovation to their home on Camden Street. Thankfully, they knew they had stumbled on something special and have taken on the burden of proceeding slowly with any new excavation, painstakingly inspecting and documenting their findings.

How much of Camden’s history is destroyed or unnoticed simply because we haven’t trained ourselves to look for the more subtle signs? If we value our history, we must learn to look for it and reflect honestly, not just in the concrete walls and brick buildings we’ve trained ourselves to recognize as historic but also the layers of soil, the wildlife, the bedrock, and the water that flows from all around.